#96

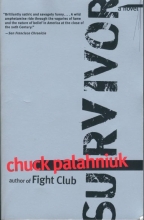

Title:

Survival of the Sickest: A Medical Maverick Discovers Why We Need DiseaseAuthors: Sharon Moalem and Jonathan Prince

Publisher: William Morrow & Company

Year: 2007

Genre: Science, Medicine

288 pages

Ignore

the title and the hype about "a medical maverick." In fact, just take

the dust jacket off. It was clearly constructed to be provocative, but

it's not accurate.

Moalem marshals evidence for the positive or

effective aspects of diseases that we might other characterize as

harmful. He is able to do so (and stick to this theme) fairly

consistently throughout the book. Afficionados of popular medical

non-fiction will recognize some of the diseases and their associated

anecdotes (there's some overlap with Meyers's

Happy Accidents: Serendipity in Modern Medical Breakthroughs,

for example). In some cases this association may not be evident until

later in the chapter--"Of Microbes and Men," for example, treats

evolutionary considerations for microbes and parasites that parallel

those for humans.

I did find myself frustrated at times by what

seemed like unreasonable dumbing down, leading to misinformation. On

page 199, for example, Moalem discusses "the cold virus." The point

would be stronger if he described the cold viruses, since there are a

multitude of causal agents for "the cold." Some of his arguments are

reductive and eliminate important considerations that are not

well-expressed in an either/or paradigm (essence vs. environment makes

multiple appearances inn this way, when the explanation is probably much

more complex than the binary choice suuggests).

Still and all,

this book was enjoyable and does a good job of eleborating on what is,

for many people, a paradigm shift in thinking about the role of disease.